While most of my day-to-day research entails writing Python code, I also make heavy use of pre-written software. Most software comes pre-compiled, but whenever possible, I like to get access to the source code. I’m going to refer to some modifications I made to pre-existing packages – you can find those in my repository here.

The most-commonly used open-source package for brain imaging is called FMRIB Software Library (FSL), which includes tools for processing MRI data, with applications ranging from motion correction and image registration, to modal decomposition methods, among many others. All of this is made available as a set of pre-compiled C++ binaries.

I needed to modify FSL’s probtrackx2 tool. probtrackx2 is a tool for generating probabilistic tractography. Using diffusion MRI, we can model the movement of water in the brain. At the voxel level, diffusion tends to be high when water moves along neuronal axon bundles, and low when moving against the myelin or in the extracellular matrix – this water movement can be modeled using a variety of approaches.

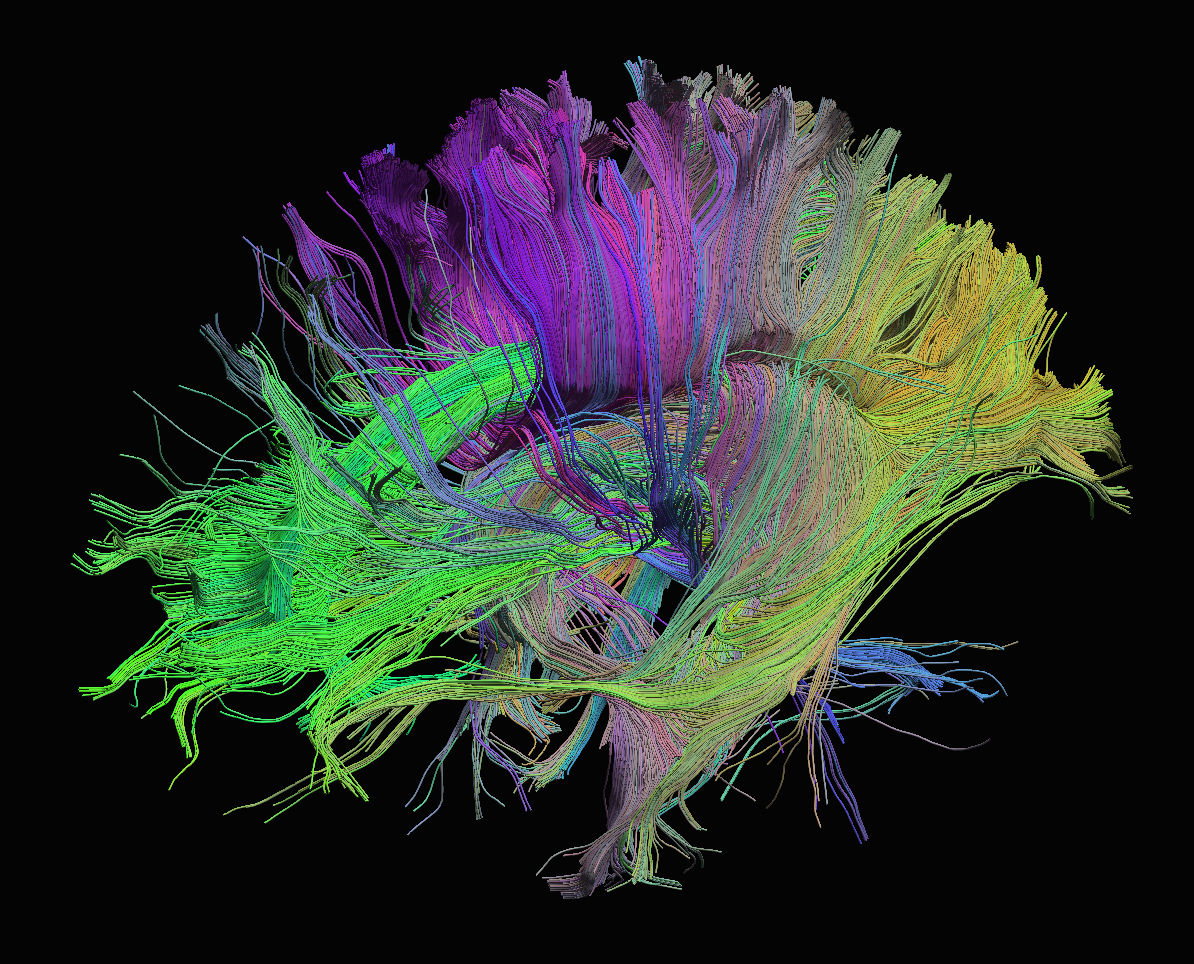

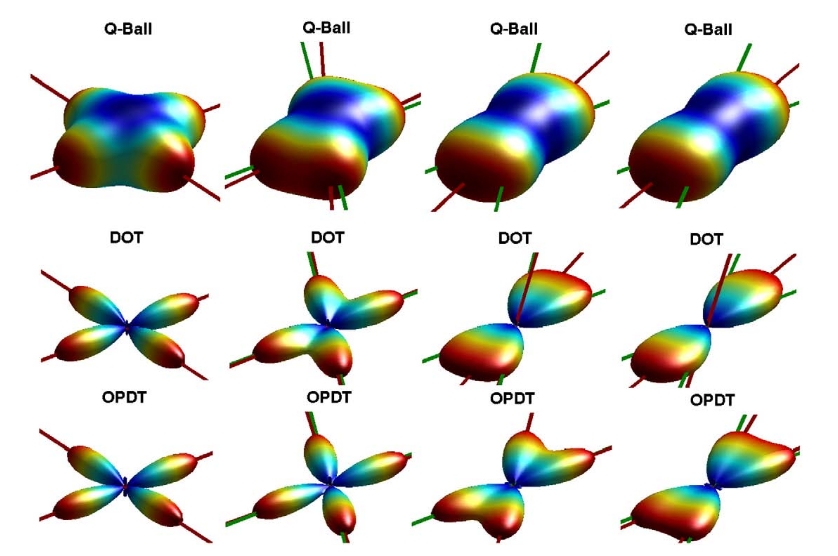

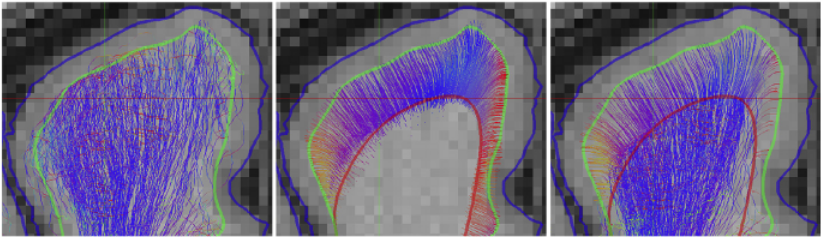

At the simplest level, the diffusion can be modeled as a diffusion tensor, where the eigenvalues of the tensor correspond to the amount of diffusion in the direction of the corresponding eigenvector. At the more complex levels, we can represent the diffusion as a 3D probability distribution function, whose marginal distributions are called orientation distribution functions (ODF), and represent these continuous functions using a spherical harmonics basis set of the ODF. Using probtrackx2, we can sample these ODFs using a Markov Chain Monte Carlo approach and “walk” throught the brain. Directions where the diffusion signal is high will be sampled more often, and we can generate a robust representation of the macroscale neuronal structural in the brain using these random walks.

The diffusion signal at the gray matter / white matter interface of the cortex is more isotropic than within the white matter (e.g. the diffusion tensors in these regions are more spherical). To reduce noise in my fiber tracking results due to this low signal, I wanted to be able to force the first steps of the streamline propagation algorithm to follow a specific direction into the white matter, before beginning the MCMC sampling procedure. Essentially what this boils down to is providing probtrackx2 with prespecified spherical coordinates (azimuthal and polar angles) for the first propagation step. More specifically, I computed the initial spherical coordinates using surfaces computed from the mesh curvature flow results of St.-Onge et al. Importantly, I wanted to make use of the probtrackx2 infrastructure as much as possible e.g. I didn’t want to write my own classes for loading in surface data, and wanted to minimally update the members of any other classes I found useful.

Jumping under the hood into the probtrackx2 code was a feat. While the software is sophistcated, it is quite poorly documented. As is common with academic code, development generally begins as a way to solve a specific problem in the lab, rather than as a package to be made available for public use. FSL has been around for a while, and grows in complexity all the time, so the initial academic-oriented mindset has somewhat propagated through their development cycles. I was able to identify the important classes and make my modifications to these three classes:

Particlein particle.h :- performs the tracking for a single streamline for a single seed, where MCMC sampling happens

Seedmanagerin streamlines.h :- manages the individual seeds, instantiates

Particleobjects

- manages the individual seeds, instantiates

Counterin streamlines.h :- keeps track of streamline coordinates in 3D-space, successful streamlines, binary brain masks, saves fiber count distributions as brain volumes

The bulk of the tracking is done using these three – the rest of the probtrackx2 code is almost entirely devoted to parsing other options and handling other input data. While I now have a lot of work to do in actually using my modifications, this foray into FSL’s source code re-emphasized three important lessons:

-

Documentation is critical. But not just any documentation – meaningful documentation. Even if you aren’t the best at object-oriented software development, at least describe what your code does, and give your variables meaningful names. Had their code been effectively documented, I could have been in and out of there in two or three days, but instead spent about a week figuring out what was actually going on.

-

You should be equally comfortable working with raw code developed by others, as you are writing your own. Do not expect everything to be written correctly, and do not assume that just because others have used a piece of software before, that you won’t need to make modifications. Be ready to get your hands dirty.

-

Do not underestimate the power of compiled languages. Most data scientists work with Python and R due to the speed of development and low barrier to entry, but each is based primarily in C (and I believe not in C++ due to timing of original development cycles). Many large-scale software packages are based on languages like C, C++, and Java. Likewise, if your work bridges the gap between data scientist and engineer, you’ll definitely need to be comfortable working with compiled languages for production-level development and deployment.